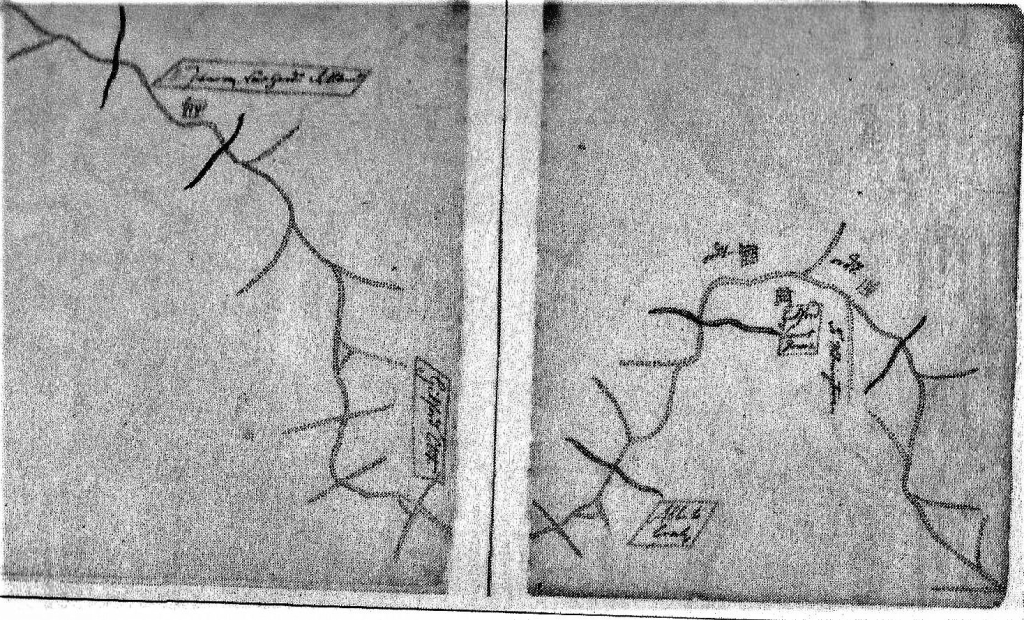

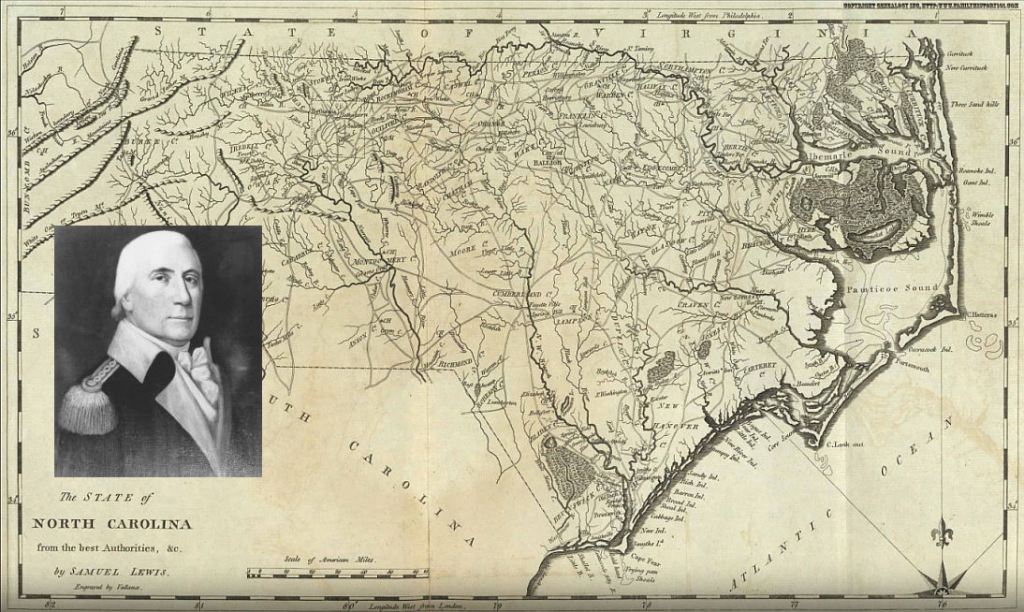

Traffic had been rerouted around the four square blocks of downtown Madison, NC and the crowd had filled the traffic-vacated streets milling about like a vat of molasses. A new word had been introduced to the general use in the months leading up to the Madison Sesquicentennial Celebration in the summer of 1968. Until they could practice a little, “sesquicentennial” seemed an unnecessarily complicated way to say 150, the number of years since the town of Madison had been created at the confluence of the Dan and Mayo rivers in the northern Piedmont of North Carolina. Once mastered, however, the word did capture for citizens of all ages that special summer of fun and frolic.

Although the headquarters of the celebration was located in a vacant store building across from the Bank of Madison on Murphy Street, it had been decided to open the first big public event in front of Dick Cartwright’s store around the corner on Market Street. It had been concluded that the “Greased Pig Race ” would be an exciting beginning and would have appeal in the entire Market area which the merchant town served. Sure enough, mixed among the local merchants and mill workers and their families, seemed to be enough bibbed-overalls, straw-hatted farmers within wagon ride of town, cast in their pejorative role as red-necks and bruising to show that they knew how to catch a greased pig better than any of these uppity city folks. A dipper of liquor had already lubricated most.

The two o’clock hour approached. Lloyd Eastlack raised his fully-loaded double-barreled shotgun under the low-hanging telephone and power lines by the street and let loose the full load. Transformed from the molasses to a swarm of flopping alligators, the human mass sprang to action even before the four small, greased pigs could be released. With difficulty, the pigs scampered off in various directions into the crowd. Women and children squealed. Men cursed with vengeance. Bib-overalls and straw hats dashed viciously through startled family groups. A captured pig brought immediate efforts to cause a fumble and a reignited scramble to retake the squealing, squirming porker dodging between shuffling legs. The pigs were lightning fast, as slick as promised. They made it well into the mass clogging each of the four blocks of the intersection before human ingenuity in the form of burlap sacks (forbidden by the rules) and pairs of burly men working as a team, succeeded in final capture. Triumphantly, without returning to any central starting point, the victors hustled their capture back to waiting pickup trucks satisfied that they had a good day’s hunt and would bring home the bacon.

“That was fun,” I said ironically until I saw the large footprint marks on the back of my seven-year-old son’s shirt and realized we had just missed a fast descent from celebration to near tragedy. “Do you know that fool, Lloyd Eastlack, shot that gun right into a string of lives wires?” I recognized that the best intent, even in public celebration, can run a close parallel to disaster at any moment.

We lived in Madison for nine years by then. In spite of being newcomers in a coagulated society. I saw very early that one of the attractions of the town to my family, was its age. Old houses, boxwoods Victorian store-fronts – all gave off an image of southern tranquility that made for immediate comfort in place. When I first recognized, and brought to the attention of my friends, that the town was about to be 15o years old, they were surprised but only mildly motivated. Somewhere between indifferent and apathetic, they were at a loss about what to do about it. I caught myself imagining Mickey Rooney urgently proposing to his friends, “let’s have a party!” That is the moment I had to look up the word for 150 and “sesquicentennial” mutated into the Madison vocabulary.

“The Music Man ” had been a Tony Award winner in 1957 and “76 Trombones” had become a high school band standard. Even without the internet, I looked up companies that were in the business of organizing and producing centennial celebrations. The John B. Rogers Producing Company out of Fostoria, Ohio, appeared to be the best known such company and a mailed inquiry brought a packet of instructions and brochures from towns that had put on one of Rogers’ productions in past years. Rogers offered themselves as suppliers of costumes, sets, lights and scripts for amateur productions as well as professional instructions for a full promotion of a centennial celebration. It seemed dauntingly out of our league but here were the small towns from all over America that had bought the service and succeeded wildly. I discussed the prospect with my fellow members of the newly-formed Madison Jaycees. The success of the Greensboro Jaycees at the time in running the Greater Greensboro Open (GGO), was a special inspiration to all chapters nearby to find something grand and glorious to promote in their community. We organized for success and approached the Mayor and Board of Aldermen.

The contract with the John B. Rogers Company provided us with a company employee who would spend three months on site to guarantee all the promotional services. The arrival of Cloud Morgan in Madison was our Music Man moment. Sesquicentennial was difficult enough. Who ever heard of a man whose first name was “Cloud?”

He was from Illinois, “not even one of us.” About average height, blond, very presentable, well-spoken and cosmopolitan beyond his 25 years. Cloud was programmed to assume the reins and focus the community on one purpose. Madison was going to put together an event like nothing it had ever seen before. They were going to raise money like they had never dreamed possible. They were going to participate individually like they had never been expected to before and they were going to do it willingly. All this was to be done according to a pre-planned matrix by John B. Rogers and we could sit back and enjoy the ride. Of course, this was done not as a dictum or as ballyhoo. It was to be accomplished just like all the other small towns had done since 1907 when the Rogers Company was begun.

The Sesquicentennial office and store were opened when Mayor Jack Sealy signed the proclamation – 1818-1968 Madison Sesquicentennial. All men were directed to grow beards or they faced jail by an official Kangaroo Kourt. Nancy Carter ran the store which was already stocked with costumes: women’s bonnets and dresses and men’s hats and ties. A shipment of Sesquicentennial patriotic bunting arrived and city employees decorated light poles and festooned streets; merchants acquired material to decorate their stores. There were bumper stickers, and “Brother of the Brush” pins.

The official celebration was to be over the 4th of July but the main focus was a pageant to be held nightly between July 1 and 6 at the football stadium at the Madison-Mayodan High School. The pageant was an activity that began as soon as Cloud had been installed at the Dolly Madison Motel. Cloud gave the committee a pre-script produced by the Rogers Company that could be modified to make it local. There were to be 14 episodes, each focusing on some aspect of the town’s history. Someone could write special music or Rogers would supply that from standard selections. The pageant was really how the whole celebration would be financed, so vigorous ticket sales were essential. The modus was to have young women compete for the title of Queen based on the number of tickets they sold. The winners and runners up would receive fabulous packages of rewards. The Queen’s Award alone would be: a mink stole (provided by the Sesquicentennial Committee), overnight stay at the Dolly Madison Motel, $50.00 savings account, silver tray, travel iron, Prolon dinnerware, Bobby Brooks swimsuit, beach towel, Jantzen sports outfit, towel and sheet set, charm bracelet, stockings, movie pass, and Merl Norman cosmetics and demonstration. The first, second, and third Princess Awards descended in value but were all well worth the effort. Local merchants were solicited for the gifts and responded with enthusiasm and Mickey Dean Anderson was the winner.

The multi-stage with three projection screens was perhaps the greatest physical challenge. Guy McCall was in charge of set construction, which had to be done the week before the pageant began on July 1st. Volunteers, mostly Jaycees, spent hours each day constructing and painting throughout the daylight, in addition to their individual work schedules.

The pageant was titled “A Heritage to Honor” and that theme was carried out in many ways, including the publication of a history of the town which Jean Rodenbough wrote and which was printed with local advertising by the Madison Messenger. The publishers of the Messenger, Russ and Mimi Spear, were “Yankees” who had come to Madison in the midst of the Depression and bought the weekly newspaper. Madison was always their “cause” – attempting to inspire a self-deprecating, Southern town to rise to its unimagined potential. Mimi had local celebrity as the daughter of the famous author, Sherwood Anderson. She and Russ could be depended on to “call Madison out” with an authority that comes from natural respect.

A variety of preliminaries primed citizens for the crescendo of the Pageant Week: a tennis tournament, an ‘Ole Fashioned Street Dance, several promenades and Kangaroos Kourts to display beard growth, and costumes. Judge “Pansy” Collins presided over the Kourt and men without beards were awarded various heinous penalties. The North Carolina Automobile Club made a special visit and stopped for display downtown on the 22nd, and a traveling Carnival made a visit for a week to the Junior High athletic field on Decatur Street, beginning the 24th.

At noon on Saturday the 29th, Mayor Sealy opened Heritage Week by cutting the ribbon at the Sesquicentennial store, surrounded by some of the young ladies vying for Queen and dressed variously from flappers to Old South belles. Young women could display their legs and married women hid their legs discreetly under hoop skirts. Churches rang their bells and a cannon was fired by an unknown bombast. Congressman L. Richardson Preyer gave a formal speech commending the town for its years of contribution to the history of North Carolina. In the evening the Queen’s Coronation Ball was held at the High School auditorium. An “old-fashioned” square dance was held at the Fairground.

On Sunday, each church recognized the anniversary focusing on their contribution to the history of Madison. As a preview of the newly completed stage on Falcon Field, a community worship service brought all the churches together.

Each day of the week was structured with a different theme: street games for children and tournaments for everything from softball to checkers and horseshoes. Each night there was a performance of “A Heritage to Honor” at the stadium as dusk settled in the summer sky. Nary a rainy night. The performance was dubbed, “a huge dramatic Historical Spectacular with a professionally directed cast of 312 people,” to perform the highlights of Madison’s colorful history – “a thrilling 90-minute performance before a 300-foot scenic background.” Each member of the cast could be expected to draw at least ten family members and friends who would fill the bleachers every night.

Episode One: “Happy Birthday, Madison,” opened with a youth color guard escorting the Queen and her four princesses onto the field to rousing cheers. Subsequent episodes recognized the town founders, the Saura Indians, the first mayor, and the Madison Academy. The “ring and spear tournament” harkened to an event popular in the Victorian years when young men on horseback jousted with long sticks attempting to hook hanging spheres instead of one another. Madison’s World War I flying ace, Opie Lindsay, was honored in one episode as were the veterans of the Second World War, many in the audience, with the tableau of the flag raising at Iwo Jima. The finale brought the full cast and stage hands forward to salute our past and pledge our faith in the future. The night ended with fireworks which got more professional with each performance.

On the 4th, the streets of Madison were cleared of automobiles, and children rode their bicycles, skated, played marbles, raced turtles, and enjoyed the frog-jumping down Murphey Street. The NC Secretary of Agriculture, Jim Graham, was the guest speaker for the dinner honoring agriculture leaders. On Industrial Day, the local mills opened to the public and families were able to see where their spouse or parents spent each working day.

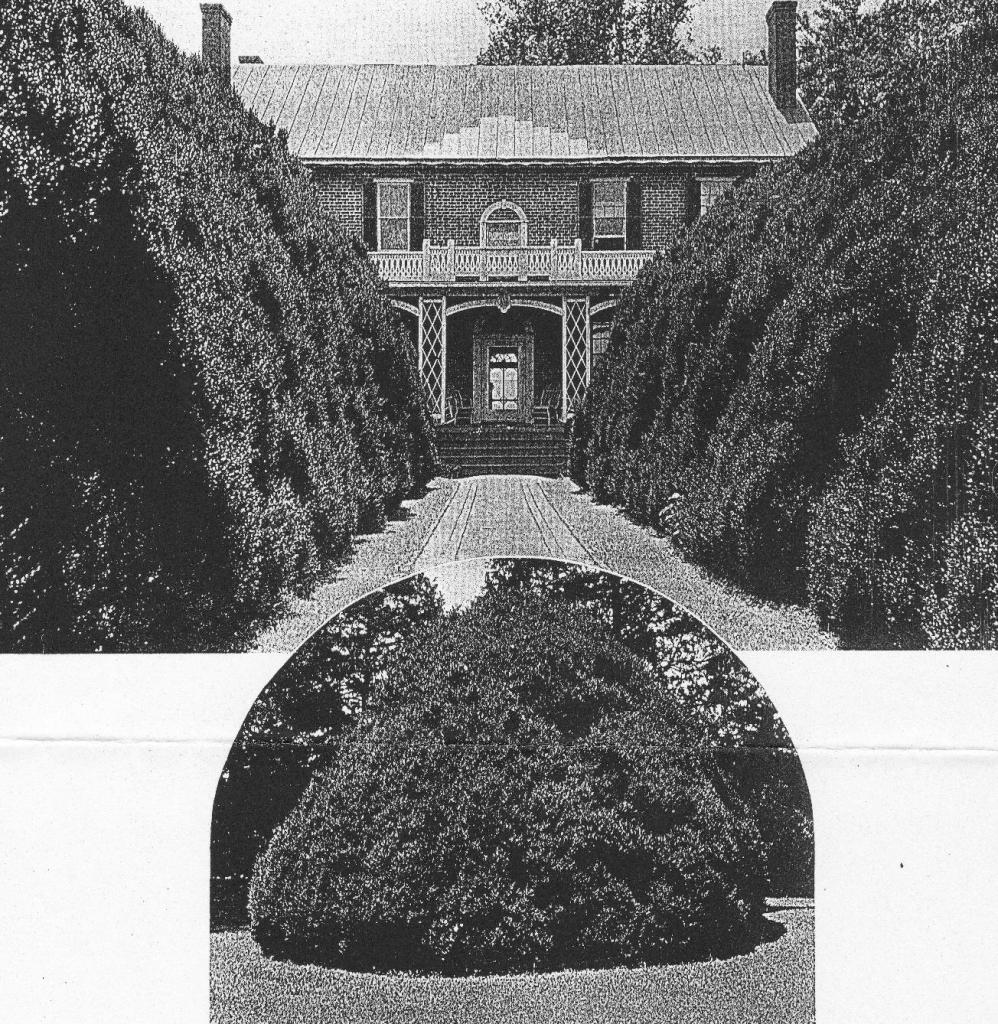

Saturday, July 6th, was “Good Neighbor Day,” the wrap-up of the Sesquicentennial. The most beautiful home was selected and a huge Anniversary Historical and Patriotic Parade wound through throngs of spectators. A Time Capsule, in the form of a baby’s casket provided by Ray Funeral Home, was buried in front of City Hall. The Mayor’s Dinner honored all the people who had organized and carried through the celebration.

A collective sigh rose from the small North Carolina community. Fatigue was overwhelmed by satisfaction. The mysterious “Cloud” had left town and everyone used the term “Sesquicentennial” with experienced ease. Madison was comfortable in the face of all the discomfort that surrounded the world. Did that comfort come from the nostalgia for a world in which America was somehow better, or was it the satisfaction that a community working within itself, together, could accomplish the perceived impossible?

On the 4th of July 2018, Madison celebrated its Bicentennial.